The first module of the online sea kayak Trip Planning Course I teach is all about navigating by chart and compass. And one of the questions I inevitably get asked during that lesson is “What about GPSs or smartphone/tablet navigation apps?”

Read more: Sea Kayak Navigation: thoughts on GPSs and smartphone navigation appsMy answer is “I love’m—in their place.” And that place is alongside, not instead of charts, compasses, and hardcopy tide and current tables. Nor am I saying that as some cranky luddite: I was a very early adopter of portable GPSs. I owned one of the first internal battery powered versions in the early 1990s, a Magellan NAV 5000D. This bigger-than-a-brick unit had no built-in scrolling charts: You had to determine the coordinates of your desired destination from a paper chart and manually key them in. Likewise, you needed to transpose the real-time position, shown as raw latitude and longitude numbers on a monochrome LCD, onto your paper chart. That was great for confirming where you were once you’d landed and weren’t moving. But when you were getting surfed along off a lee shore, trying frantically to determine how close you were to sandbars lurking beneath the muddy waters of a shallow Arctic sea? Rather too much latency (as in “The late Philip Torrens was found not far from the reef that had capsized the kayak…”). So by today’s standards, that GPS was risibly clunky (It’s literally a museum piece now.) But by the standards of the time, it was revolutionary. It was an incredible help in finding our way through the often featureless Canadian Arctic.

Since then I’ve almost always owned and carried a GPS of some type while kayaking anywhere other than in my backyard waters of English Bay in Vancouver, BC. As with all consumer electronics, features have expanded as cost and size shrink. Today’s units can hold integrated scrolling charts that show your position relative to the land and seascape in real time, just as the maps app on your smartphone shows a rolling roadmap when you’re driving.

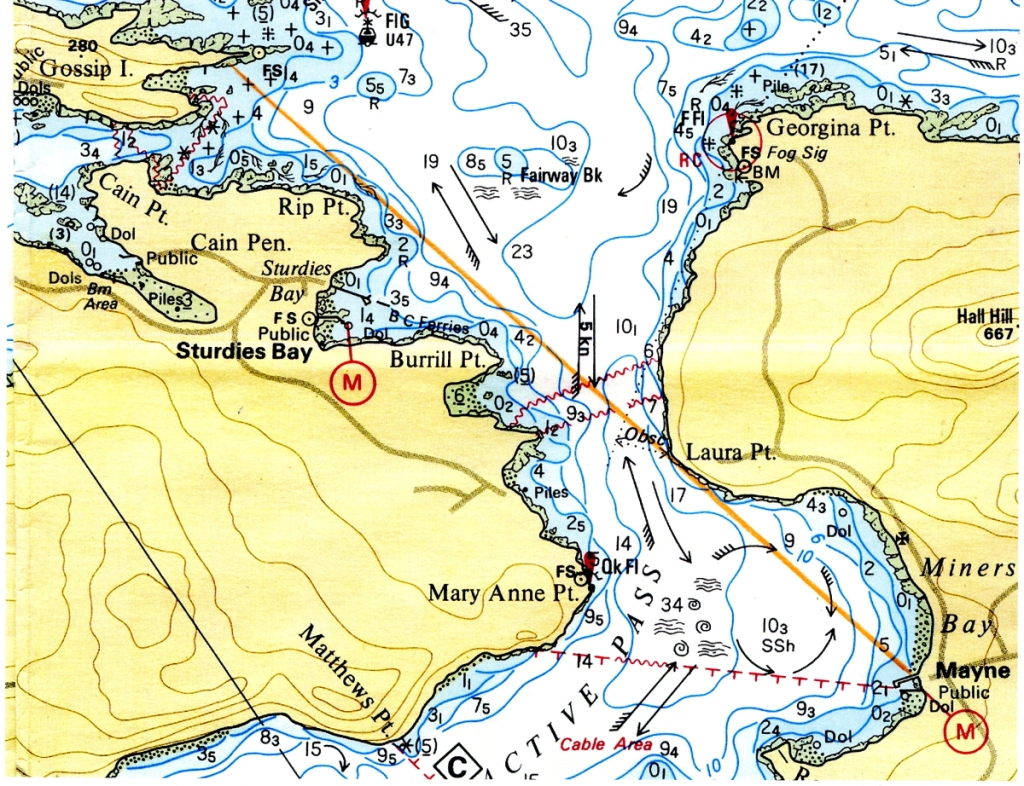

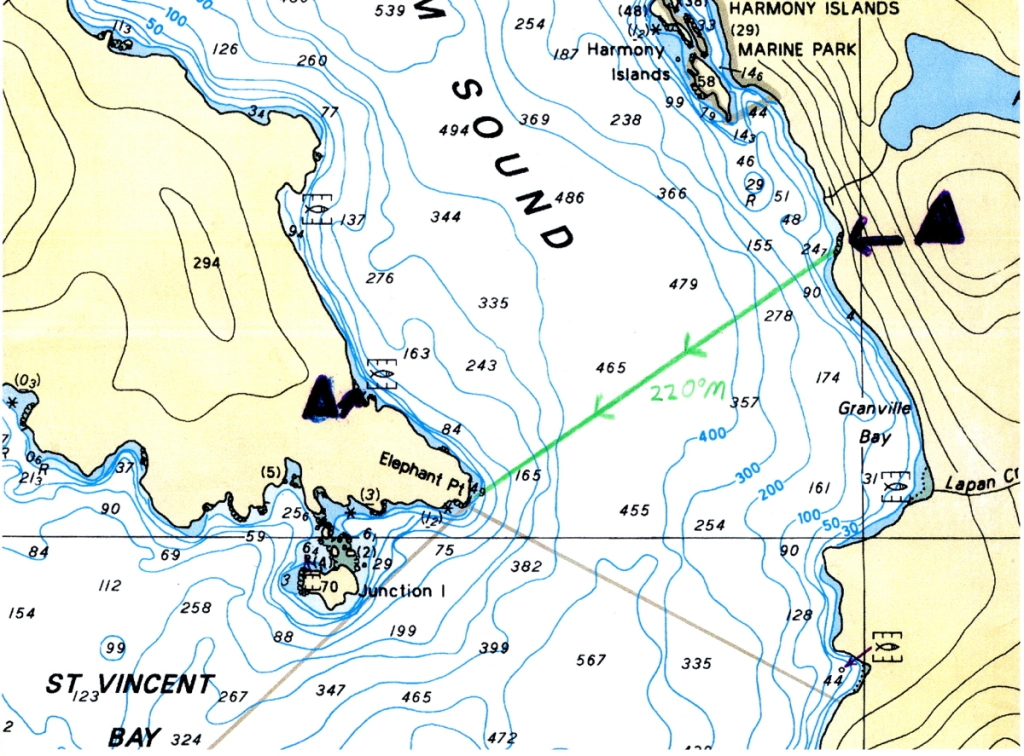

One of the functions I like best and use most with GPSs is their ability to automagically offset for drift from wind and current in real time and guide you along a fairly straight line to your destination, as opposed to a much longer arc.

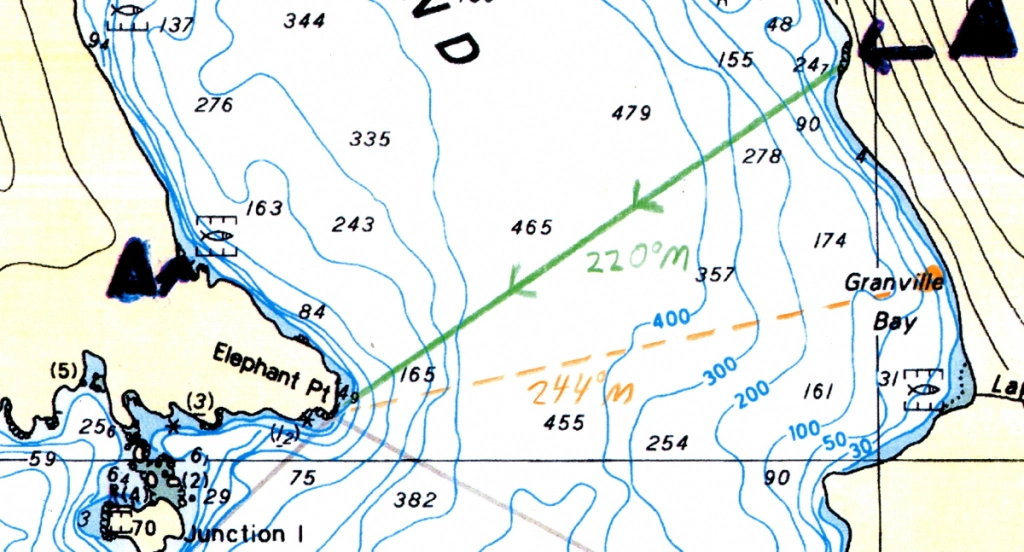

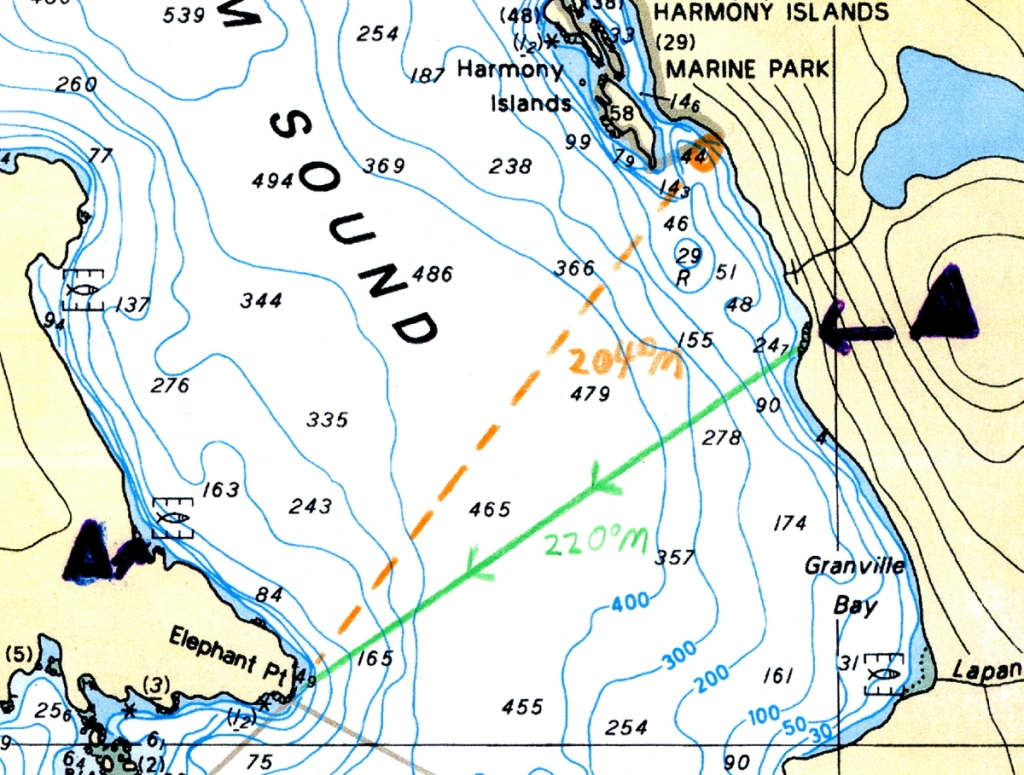

There are formulas for predicting the upstream angle you should ferry given a particular current speed, crossing distance and paddling speed—see David Burch’s excellent Fundamentals Of Kayak Navigation. But both current speed and paddling speed can vary over the course of a long crossing. Throw in the wildcard of wind, and holding a straight course gets pretty problematic. Likewise, there are techniques for using ranges and/or changing compass bearings to detect and offset drift. But they rather rely on being able to clearly see specific real world features, which won’t always be possible, especially when your landfall is on or over the horizon. So the longer the crossing, the better I like my GPS.

GPS’s real-time drift detect-and-correct is handy even over shorter distances when I’m kayak sailing. Because kayaks aren’t keel boats, they’re subject to a lot of drift with a sail up, especially when on any point of sail other than running before the wind. With more complicated rigs such as the Falcon Sail I’ve got on my rudder kayak, the crew is often fully occupied trimming the sails properly and has little spare bandwidth for monitoring drift. The GPS helps me point my kayak just far enough off or across the wind to get where I want to go, without stalling by pointing unnecessarily high upwind.

Another very cool feature on many GPSs and apps are the built-in tide and current tables. Often these are not mere numerical columns with times of lowest and highest waters and minimum-maximum current speeds, but also graphs that let you easily determine precise water depths and current speeds at any interim between the highs and lows. That’s really handy for finding tent sites on the beach that won’t feature ensuite swimming pools at midnight, or for deciding just how long after slack water it’s still safe to run Suckemdowne Narrows.

Although it’s great to let the GPS magic box do all that math for you, you should retain a working knowledge of formulas such as the rule of twelfths, the rule of thirds, and the 50/90 rule, plus hard copies of the tide and current tables for the areas you’re paddling. This will both improve your intuitive understanding of what the magic box is telling you, and ensure you’re not left helpless if the magic ever dies due to exhausted batteries or saltwater leakage.

I personally have a strong preference for freestanding GPS units over phone or tablet apps. Part of that is probably just intellectual inertia: I’ve been using GPS-specific devices for decades and am very familiar and comfortable with them. But there are practical reasons as well: I prefer actually owning the unit and the data in it to renting an app on a subscription basis. I’ve heard too many horror stories of companies nickel-and-diming their subscribers with fee increases, reducing or bricking functionalities when pushing out upgrades you can’t opt out of, or orphaning apps when they go out of business. I also prefer not having all my electronic eggs in one basket: if I lose my navigation functions for whatever reason, I don’t want to have also lost my phone functions, or vice-versa. Last, but far from least, it’s much easier to operate real buttons than a touchscreen through the plastic window of a waterproof soft case.*

*You absolutely do want cases for your GPSs and phones, notwithstanding any manufacturer’s claims about their integral waterproofness. The one time I insufficiently sealed my soft case, then knocked it into the sea while docking, the supposedly waterproof GPS inside drowned itself in a fit of pique.

Despite my personal preferences for stand-alone GPSs, I can see the case, so to speak, for navigational apps such as Navionics or savvy navvy. They make for one less physical gadget to buy and carry (and for reduced end-of-life e-waste). Plus, to a generation accustomed to downloading apps for everything from ordering dinner to help with stargazing, I’m sure that instantly adding one more functionality to your phone just feels simpler and more intuitive.

That said, I just recently upgraded my ancient (but still operating) Garmin GPSmap 76Cx to Garmin’s GPSmap 276Cx. The new unit is a bit bigger than the old one, which sounds like a retrograde step. But that’s actually a feature, not a bug: the significantly larger screen makes chart details much easier for my elderly eyeballs to read.

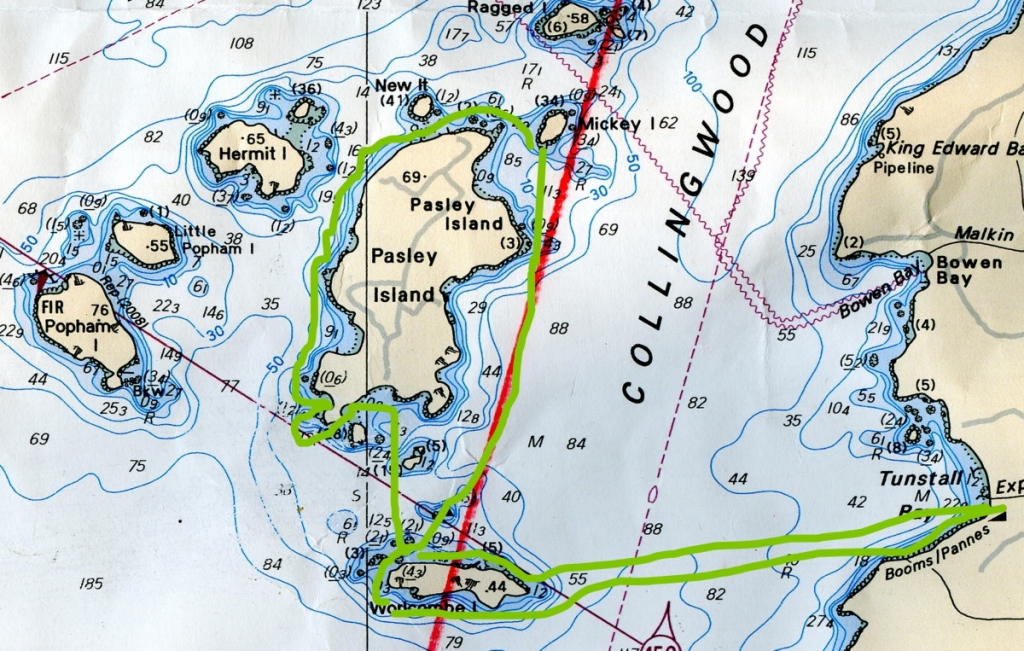

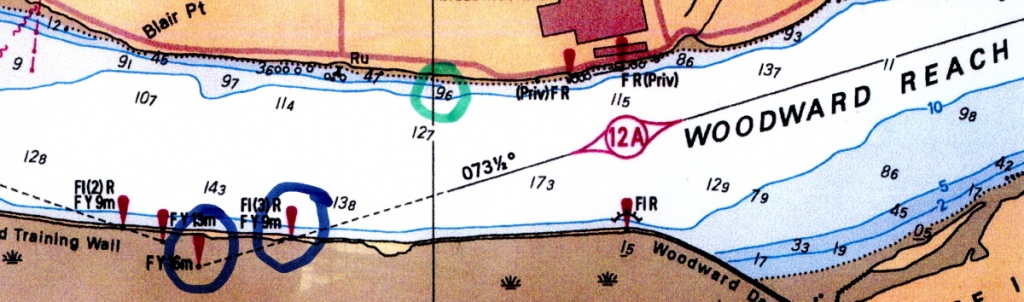

Which leads us to an important way GPSs work best alongside hardcopy charts rather than in lieu of them: even the larger screen on my new GPS is only about 2.5” x 4.25”, while the “screen size” of my smallest chart bag is about 9” x 12” (and I have larger ones). Meaning the paper chart covers more area in more detail than the map page of even the largest tablet you’d care to mount on your foredeck. And all at-a-glance, fully sunlight-readable, no zooming or panning-and-scanning required. So when you’ve blundered into the thick of Shipwreck Rocks to find larger-than-forecast swells running, you can use your GPS’s chart page to determine your precise position in relation to immediate local hazards, and the big picture from your paper chart to ensure that the escape route you’re improvising doesn’t turn out to be a literal deadend.

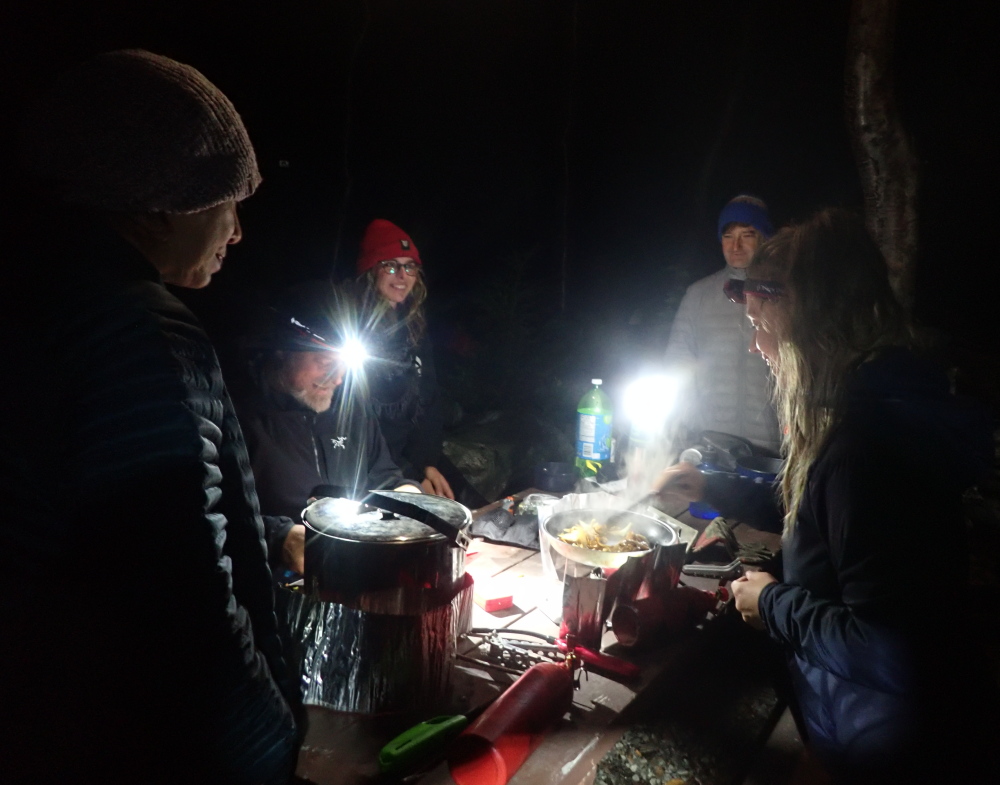

Less urgently, but still usefully: during pre-trip planning at home, you can use the big screen of your computer to scroll electronic charts, and point-and-click waypoints and routes to download to your GPS. But you won’t have that computer with you in camp as you plan the next day’s voyage, often switching things up from your original ideas based on field experience of the area. Rather than just squinting through the letterbox slot of your GPS screen, use your paper charts for big picture planning, then scroll to add any additional required waypoints on the GPS.

Similarly, I prefer to use my GPS in conjunction with, not in replacement for, my old school magnetic compass. Why? Imagine yourself paddling a long crossing directed solely by your GPS. See how pretty is the pixel picture it paints of the virtual world on its chart page! See how it counts down the distance and ETA to your destination in such encouragingly bite-sized increments! See how precisely its compass arrow points the way! See the spiked deadhead log you’ve just punctured the bow of your boat against! Oh, wait – why didn’t you see that? Because your eyes were magpied by those shiny moving screens, distracted in the same way that drivers become intexticated by their phones.

Less lethally, but still tragically, there’s much else you might miss when bowing to the electronic idol on your spraydeck shrine: the bright flash of a passing puffin, or the soft roil of migrating humpbacks, or a baby sea otter bobbing expectantly as it waits for mom to surface with breakfast, or any of the million-and-one things you are presumably out there paddling in order to experience.

How to avoid missing all that? Set your GPS to display the compass bearing to your target waypoint (use the settings menu to ensure it’s displaying a magnetic bearing rather than a true North bearing, and that it is autocorrected for local magnetic variation). Check this reading periodically as you paddle, but actually steer by the bow compass on your kayak. Result: with your head up and your eyes focused for distance, you’ll have much expanded situational awareness (and much reduced susceptibility to seasickness). And if the GPS should decide to shit its pants (sorry about that technical mumbo-jumbo) mid-crossing, reverting to the deck compass for navigation is smooth and panic-free, since you’re already using it to steer to the last known bearing to your waypoint. (Based on how that bearing was changing up to the point of GPS failure, you’ll know whether you were being drifted to the left or to the right, and hence which way to turn to find camp once you hit the shoreline.)

BTY, Class D/Class H handheld marine VHF radios have integrated GPSs, and therefore offer navigation pages with a compass pointing to your selected waypoint. But none that I know of offer full marine chart pages (yet – the market is always evolving!) So the navigation experience they offer looks and feels like that of stand-alone GPSs from two decades ago. Also, I like to have my VHF in a holster on my PFD, rather than on the deck, in case of separation from my kayak (When it comes to emergency equipment: If you don’t have it on you—you don’t have it!) So for those reasons, I’d never rely on my radio as my primary electronic navigation tool. That said, if I found myself in swirling fog and currents, uncertain of my position and with my primary GPS inoperable, I would absolutely use the VHF GPS for my Hail Mary play.

Aside from the sheer satisfaction of using the traditional skills and technology of charts and compass, and the sense of connection that gives me with all the generations of seafarers who have come before me, there is that practical benefit of redundancy in the event of equipment failure. (I felt a smug sense of vindication when I learned that the US Navy, after having skipped celestial navigation training for an entire generation of officers on the grounds that GPS had rendered it obsolete, brought back sextant schooling several years ago.)

So think of compasses and charts and hardcopy tide and current tables not as low tech but as highly robust tech. If none of them had previously existed and someone introduced them today as a navigation suite that doesn’t depend on satellites or subscriptions, never needs batteries, is pretty much impervious to salt water damage, and is immune to spoofing*, that would sound pretty damn amazing. As it is!

*With the exception of the “self spoofing” you can accomplish by packing your steel hatchet in the bow compartment just under your deck compass. Or by letting the magnetic clasps on your waterproof phone case swing too close to the hiker’s compass in your chart bag. You deviants!