January 21, 2024

The relentless icy rain this Sunday morning was pretty uninspiring. But we thirteen Jericho Beach Kayak guides had committed to a group daytrip weeks before. So we had a certain professional pride (plus a gender-neutral machismo) that dissuaded any of us from chickening out in front of our peers.

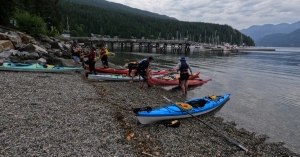

We waded through a small ice-water lake in front of the Jericho Beach Kayak hut to schlep the boats out to the roof racks waiting on our vehicles (the prudent—or at least the so-equipped—of us had heeded EJ’s suggestion to bring boots for this portage.)

Our little car convoy made fine time to the Horsebay Ferry Terminal, and caught the 10AM something boat across to Nex̱wlélex̱wm/Bowen Island. Enroute, we had a quick huddle in the passenger lounge to confirm launching, the paddle plan and radio channels.

As if to reward us for our perseverance, the rain stopped just as we launched from Tunstall Bay at noon. On the cliffy south side of the bay, a frozen waterfall testified to the unseasonably cold weather of the previous week.

As we approached Worlcombe Island, we could see vast flocks of large birds gyring above the treetops. They proved not to be vultures lurking for under-prepared kayakers, but eagles young and old. (They’re clearly visible at this point in my buddy Mike’s video of our outing.)

We alit a little after 1PM in a small bay at the southwest tip of Pasley Island. In summer, I wouldn’t bother firing up a stove for lunch, but in winter, it’s nice to stoke the inner fires with pre-warmed fuel. So my trusty WindBurner stove came into play. It was not only mucho fast but also provided much amusement for my tripmates, as the vast clouds of steam made it look like I was either improvising a sauna or preparing to do a magician’s disappearing act.

It being the offseason, the homes on the upland above our picnic spot were not occupied. This was fortunate, since it meant that those of us who lined up facing the southern rockwall to take the necessary pre-launch precautions to ensure our drysuits would remain dry for the next leg of the voyage were not accosted by irate cottagers.

On an offshore rock near the northwest tip of Pasley, we spotted a bleached white skeleton. This was not a kayaker who’d been marooned by an insufficiently secured boat, but a brilliant bit of sculpture installed by an unknown artist for the delight of passing boaters. It even included an appropriately wind-tattered pirate flag.

Somewhere between our boney friend’s reef and Mickey Island, the rain began to fall intermittently. But it had held off for our lunch stop and was pretty tolerable while we were buttoned up in our boats and pumping out body heat with every stroke.

As we bobbed in the lee of Mickey Island, confirming our course home and who was leading the next leg of the trip (me, as it happened), swooping and diving seagulls just off the point on Pasley Island south of us showed something was afoot (or perhaps, afin). And as we got nearer, swirls and splashes from beneath the sea, like reversed raindrops, confirmed that fish were being herded up from below. Sure enough, enormous thick brown necks suddenly broke the surface, accompanied by huffs and snorts. (As an aside: I’ve been within paddle-poking distance of Orca more than once over the years, but I continue to be more wary of sealions than killer whales. Still, I comforted myself with the idea that if they decided they were tired of seafood and wanted a little red meat, the odds were only one in thirteen I’d be dinner!) The sealions are best visible at this mark in Mike’s video.

Switching leaders once more at the western tip of Worlcombe, we handrailed along its south shore, encountering more sealions on route. They proved pretty camera-shy, appearing only in the distance anytime I had my Go-Pro in hand.

We landed back in Tunstall Bay a bit after 4PM, with a rain falling so steadily I opted not to change out of my drysuit, but to drive to the ferry terminal still wearing it.

The last of us rolled onto the five-something ferry just moments before it sailed, as if it were our own personal, private transportation. Upstairs in the passenger lounge, we ambushed one of our number, whose birthday it happened to be, with donuts and singing.

After offloading the boats back at Jericho Beach Kayak, we supped at the Wolf And Hound. It’s amazing how many of our adventures end there. It’s almost become our off-season office!

Thanks to all my colleagues for the pleasure of their company, and to Mika, Chris, Natalie, Tomo, Warren, and EJ for sharing pictures for this post.